On 27 February 2013, I gave the presentation “The Forgotten of Web Accessibility” at the 28th Annual International Technology and Persons with Disabilities Conference (CSUN 2013). Many thanks to the people who attended the session for their interest, comments and questions.

The slides from the presentation and the speaker’s notes follow:

Speakers notes

Slide 1

I spend a fair bit of my time watching people use the web, sometimes just out of interest or for personal research projects, but often because I am paid to.

Last year, I was asked to test how well people from a specific group within the community were able to use a site that had been made from them. And, a comment from one of the participants piqued my interest, leading eventually to the subject of this talk.

Slide 2

“I don’t use the web” is not a response you normally get from someone in front of a computer about to undertake some tasks using a website.

I was perplexed, here we were sitting in the computer room of an organisation that provides support for some of the most marginalised in the community, and I knew the participant had been recruited because he regularly visited the centre to use the internet.

“So, what do you do here”, I asked.

Slide 3

“I use Facebook, and sometimes to send email”, was the reply.

This got me thinking, and so for the remaining test sessions, rather than just asking a general question about how often someone uses the web or internet, I would have a bit of conversation with the participants about what they did online.

Slide 4

Hang on, some of you might be thinking, or screaming to yourself. This sounds like usability. What’s it got to do with accessibility?

Well, I don’t believe accessibility and usability are mutually exclusive. And furthermore, I am fearful that while the desire to separate the two might be beneficial to some assistive technology users, it could have profound consequences for some other web users who find accessing content difficult.

I am particularly concerned that older and/or novice web users as well as people with cognitive or learning difficulties will find it increasingly difficult to access web content if we don’t foster an approach that embraces both usability and accessibility.

Slide 5

Over the last decade the efforts of the W3C, accessibility advocates, and regulators in many countries have resulted in a web that is more accessible for many people, particularly those who rely on different assistive technologies.

A significant aim in the development of WCAG version 2 was to have guidelines that were technologically neutral.

In addition, the desire for a more reliable system of compliance testing meant that the inevitable blurring of the boundary between usability and accessibility was be avoided as far as possible. To quote the WCAG document:

“There are many general usability guidelines that make content more usable by all people, including those with disabilities. However, in WCAG 2.0, we only include those guidelines that address problems particular to people with disabilities.”

Slide 6

It is now much easier for people in many countries to go online. The relative cost of computers and internet connection has fallen significantly, and now free internet access is available in social spaces such as libraries, cafes and community centres.

Part of this race down the information superhighway, has been the growing use of the internet by government agencies to deliver government services, so much so that in some countries like Australia, it is becoming increasingly difficult to access some services if you are not able to use the web.

However, in the rush we are in danger of sometimes losing sight of the fact that not everyone can participate in this online revolution; a combination of geographical, financial, psycho-social and cognitive factors means there is still a great gap between the digital haves and have-nots.

The total number of internet users is increasing all the time, but perhaps more important is the increased diversity of people who are online. It appears however, that many website owners and developers are either reluctant, or unable, to make sites that cater to the needs of these different sections of the community.

Slide 7

Although there are still vast disparities in the well-being of our fellow global citizens, overall people are living longer.

- In 1950, about 8% of world population over 60

- 2005 it was nearly 10%

- And the UN estimates that by 2050 it will be 22%

In developed countries, like Australia and the US, this increase is more rapid, where for example, in all the years up to 2000 there were more people under the age of 15 than over the age of 60, but since then the situation, has switched and the gap is growing wider each year.

In the developing world, falling birth rates and improving economic circumstances is also causing shifts in the population profile, but at a slower rate.

Reference: UN World Population Prospects (2006) http://www.un.org/esa/population/publications/wpp2006/WPP2006_Highlights_rev.pdf

Slide 8

And, older people are increasingly going on line.

Research by PEW Internet into use of the internet by people in the US over the age of 65 found that :

- About 15% were using it in 2000

- 38% by 2009

- And by 2012 the percentage of over 65s had increased to 53%

Reference: Most recent PEW report (June 2012) http://www.pewinternet.org/Reports/2012/Older-adults-and-internet-use.aspx

I don’t have comparable figures for Australia, but in 2011 the Australian Bureau of Statistics released the result of their Online at Home survey conducted a couple of years earlier.

It reported, 31% of people over 65 were online, with about half using the internet daily.

Reference: ABS Online at Home http://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/Lookup/4102.0Main+Features50Jun+2

Slide 9

At the CSUN 2011 conference I gave a presentation called “Improving Web Accessibility for the Elderly”. The presentation considered how people over the age of 60 use the web, how much they use it and what they use it for.

We surveyed or tested a total of 155 people over the age of 60, and the main reasons they gave for using the Internet were:

- Keeping in touch with family and friends, and

- Finding health related information.

These findings are similar to those reported by PEW Internet in 2010.

Most said they experienced difficulties when attempting to use the web and I will talk a little more about this in a few minutes.

Slide 10

According to the W3C Web Accessibility Initiative, the main age-related impairments that older people have which could affect their ability to use the web include:

- Vision loss or decline – e.g. fall in the ability to read and distinguish between colours.

- Reduced physical dexterity and fine motor control, making it difficult to use a mouse and click small targets

- Hearing loss making it difficult to hear generally and separate what you want to hear from competing background sounds, as occurs when listening to a conversation in a crowded room.

- Decline in cognitive ability including reduced short-term memory and difficulty concentrating.

The WAI advises that since these issues overlap with the accessibility needs of people with disabilities, sites that are accessible to people with disabilities will be more accessible to older users as well.

Well yes, sort of:

Those issues relating to declines in vision, hearing and physical abilities may be well catered for under the existing WCAG arrangements.

However, those relating to a decline in memory or the ability to concentrate, understand instructions and make decisions are not well catered for.

Many issues similar to these maybe be experienced by a wide range of people, and not just the elderly. For example, novice web users or people with reading difficulties.

I now want to spend a few minutes talking about a couple of projects I have been involved in that touch on some of these issues.

Slide 11

In 2007, I was asked to test the usability and accessibility of a website for people who were homeless or in public housing. It was expected the site would be primarily accessed from computers and/or kiosks in government offices and welfare organisations.

Five years later, in 2012, I had an opportunity to review another site prepared for a target user group where there was some striking similarities in terms social marginalisation.

During the 2012 project, as a result of comments like “I don’t use the web, I use facebook”, I found myself reflecting on some of the changes in how the test participants of today understood and used the web when compared to those five years earlier.

(For reasons of privacy and client confidentiality I cannot provide specific details.)

Slide 12

With both projects, many of the participants were from lower socioeconomic status groups in the community and included a significant proportion who are largely marginalised in terms of education. As a result, many had lower-level reading abilities and limited access to computers and the internet when compared to the general community. Also, in both projects a number of the test participants were over the age of sixty.

However, as we will see, the online abilities and experiences of the participants from the two projects were quite different.

Slide 13

In 2007, while all the test participants had used the internet, the amount of use was generally very limited and very few had the ability to access the web on a regular basis. Only 28% went online for five hours or more per week

However, after being introduced to the test-site they appeared to be genuinely interested in using it to find information and actively explored the various navigation options. Most appeared to develop an understanding of the site navigation system with relative ease and participant comments included:

- I just love using the computer – I didn’t realise there was so much you could do.

- I thought it was tricky at the beginning because there is all these different sections to look at for where to go (for information)

Slide 14

As might be expected, all the test subjects in the 2012 project had greater opportunities to access the web than those in 2007.

50% of the participants reported using the internet every day, and all-up 80% said they used it at least once a week. Most went online either via computers owned by family members and friends, or through various community centres with computers and free internet access.

Slide 15

Given greater opportunities to use the web, for many of the 2012 participants going on line was rather ho-hum, as you might expect, and not the exciting new adventure that the participants from five years earlier seemed to find it.

However, this “been-there/done-that” attitude seemed to translate into less excitement or curiosity about the technology. The web was just about finding information, such as sports results or what your friend is doing and not something to experience.

Now this in itself is not worrying, or even particularly interesting, but an apparent lack of interest, or difficulty, many 2012 participants had in learning the basic concepts of website navigation I did find interesting.

Slide 16

The basic structure of websites and standard navigation systems seemed to confuse at least some of the participants in 2012. When undertaking tasks with the site, most participants either did not use the main navigation menu, or did so very reluctantly.

Even after using the site for about an hour several were still confused by the common navigation terms “Home” and “About”, and tended to see them as relating directly to themselves or their situation, comments included:

- Home is that Australia or where you live?

- Is Home something to do with the home you came from?

- What is About? Is that about the information you are looking for.

- What’s the difference between Home and About?

Slide 17

This apparent decline in the ability to understand, or at least a willingness to learn, the navigation systems common to many sites may not be confined to novice web users or people with lower-level reading skills like those involved in the 2012 project.

Instead, an emerging ‘Facebook effect’ may help explain why some regular web users today are less likely to participate in the exploratory, web-surfing behaviour of the past.

Slide 18

Facebook recently announced its one billionth account; that is a lot of people, even if all these accounts do not represent separate individuals, and so it is reasonable to assume that Facebook could have an effect on the way people perceive the web and operate in it.

On Facebook (and other social networking sites such as Linkedin) focus is on the individual and their friends, and the navigation systems reflect this focus with the link ‘Home’ taking the user back to their first page, or Wall.

Within this context, it is possible that there is a growing uncertainty about common site navigation labels like ‘Home’ and ‘About’, and this uncertainty requires them to think more about selecting one of these items and hence a reluctance to do so. As Steve Krug famously said “don’t make me think!”

This breakdown in a common understanding of what is website navigation is likely to be exacerbated by the increasing use of application-based interfaces for a wide range of web activities ranging from banking to train timetables. And, who knows what the long-term impact will be of the move to touch screens with swipes, pinch to zoom etc.

Slide 19

When it comes to finding information on the web in general, or on an individual site, over the years I have noticed that many web users are either ‘surfers’ or ‘searchers’.

Of course, this is not a hard and fast rule, and all of us probably indulge in both at times, but it seems that when seeking information some people are more likely to surf from site to site and use the navigation within sites, whereas with others, the first inclination is to search.

In 2004, Google accounted for less than 50% of all search engine use and the next most popular at the time, Yahoo, was at 26%. But by 2012, 83% of searchers use Google, with Yahoo still second, but at a distant 6%.

Google now logs about 2 billion search requests a day, from approximately 300 million people. And, for many people Google is the standard entry point to pages deep within websites. Why bother with learning how to use a site to find what you want when Google will do it for you. To quote one recent test participant:

I normally just type the words in Google and it comes up. I always select one of the top results, because if I type a good question it will be there.

But, what happens if it’s not there?

Slide 20

A combination of this growing reliance on Google, and a Facebook effect, where the preoccupation is on the individual, may mean that it is time to reconsider some basic usability and accessibility principals. And in particular, the potential accessibility impact this may have for web users with cognitive impairments and/or limited internet experience.

I feel when the struggle some people have in understanding basic website concepts is combined with the growing use external search engines to locate information within a site, this must have implications for WCAG 2, in particular, “Guideline 2.4 Navigable: Provide ways to help users navigate, find content, and determine where they are.”

Slide 21

In a practical sense I think there are a number of issues that need to be considered:

- Should we continue to use common navigation labels like “Home” and “About”? Depending on the primary audience for a site, it may be better to be more specific, for example by using the name of the organisation.

- Perhaps we should give greater consideration to Success Criteria 2.4.8 (“Location: Information about the user’s location within a set of Web pages is available”) and associated Technique G65 about the use of breadcrumbs. This Success Criteria is at level AAA and so often ignored, but since users are increasingly going directly to internal pages, sometimes deep within a site, it could help them determine where they are.

- Maybe there should be a slight shift in the focus of SEO from promoting goods and services (content) to actually helping people find what they want within a site.

Slide 22

On a slightly different note, with the ubiquitous web of today it is hard to ignore the warnings and tragic stories, like those associated with Nigerian scams and cyberbullying. And, fear is one thing that did seem to get through to the 2012 participants. But whether their fears are always rational or justified is another question.

For example, one of the test tasks in 2012 involved the participants finding a link to some information in the form of a PDF. The link contained the word “download” and this led to about a quarter of the participants indicating a belief that downloading anything would be a serious security risk. For example I heard;

- I always avoid anything that says ‘download’. It’s safer.

- I don’t think I would download this. I don’t download in case I get into trouble.

And in the case of this last comment, trouble came in the form of condemnation from more tech-savy teenagers who have become self-appointed internet gatekeepers.

Slide 23

Now, rather than the differences I had noticed when testing these two site, I would like to look at a similarity.

The one striking thing the 2007 and 2012 sites had in common was a fondness for words, often big words and lots of them. And, in both projects, many test participants found the content difficult to read and understand.

Slide 24

Although tools for testing reading levels are rather crude, depending as they must on components of the text that can be measure mathematically, they can provide an indication of what is required.

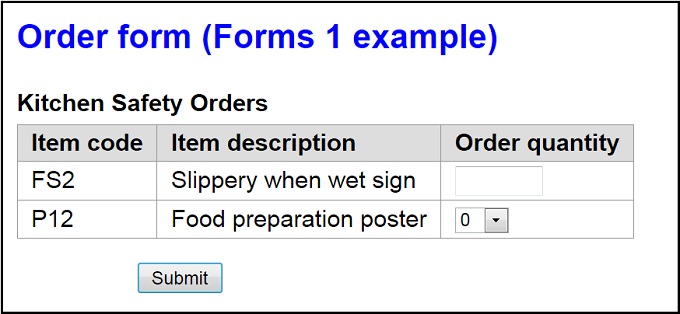

And, I sometimes use these tools to help communicate to the owners of sites why they should look at ways of making their content simpler. For example, this table provides the results from testing the reading level of a sample of pages from the 2012 site using two measures of readability:

- Flesch Reading ease – higher the score the easier content is to read. Maximum score is 100 and for plain or simple English a score of 60 plus is advocated.

- Flesch-Kincaid grade – measure of number of years of school required to understand the content. (Maximum score is 12).

Not surprisingly numbers like 49.5 and 9.91 for the 2012 pages are not particularly meaningful to most clients, so I also tested some articles on the site of Daily Telegraph, a mass circulation tabloid newspaper in Sydney to provide a comparison.

And, as you can see when a reading ease score of 60 is considered necessary for easy reading – the Telegraph scored 68.7 compared to 49.5 for the tested site.

And, when it comes to the number of years school required to understand the content the difference is even more stark – less than 5 compared with nearly 10.

Slide 25

It can be very hard to get a firm grip on how many people have reading difficulties. On one, rather simplistic level, Australia has a very high literacy rate; 99% can read and write according to Wikipedia, along with the US, UK, NZ, Canada and many other similar countries.

However, a more realistic impression can be gained from the ‘Adult Literacy and Life Skills Survey’ conducted by the Australian Bureau of Statistics in 2006, as part of an international study by the OECD.

This survey looked at a number of literacy components, or domains, using five levels of ability. And found:

- 17% of the adult population had literacy at, or lower, than the minimum level.

- And 46% were at a level that was below what the survey developers regarded as the “minimum required for individuals to meet the complex demands of everyday life and work in the emerging knowledge-based economy“

And, I expect the results in the US would be very similar to those in Australia.

I know how difficult it can be to get a handle on the extent of literacy problems in the community. For many years ago, in a pre-web life, I was commissioned to do research and prepare resources for the UN International Year of Literacy in 1990.

And, I have two strong memories of this research: First, the extent to which reading and writing problems are under reported in the community; And, second the extremely diverse and complex nature of the issue.

Slide 26

Over the years, there has been a significant under reporting of the number of people who have problems reading, due in part to the erroneous assumption that people who find reading difficult are somehow stupid.

There are many reasons why some people have reading problems and of course some relate to intellectual impairments. But there are a variety of other causes, in some cases it might just be the simple fact that they didn’t have the opportunity to learn or problems with their vision, but it could also be due to wiring problems in the brain, inability to identify or sound-out different components or words, the poor processing of visual information and not forgetting the sometimes contentious issue of dyslexia.

Whatever the reason, there are many examples of brilliant and highly successful people who have, or had, difficulties reading including:

- Innovators like, Alexander Graham Bell and Thomas Edison.

- And scientists like Michael Faraday and Albert Einstein.

When it comes to the accessibility of web content, the individual causes of reading problems is not particularly relevant. What is important however is the fact that in countries like Australia, somewhere around 20% of the adult population find reading text difficult.

Slide 27

WCAG 1 explicitly recognised the problems faced by people with reading and learning disabilities with a Priority 1 Checkpoint; “14.1 Use the clearest and simplest language appropriate for a site’s content”.

Sure, this checkpoint was hard to interpret, hard to measure and often ignored, but at least it gave us something to fight with.

In the desire for accessibility purity, and guidelines that it is hoped could be more reliable tested by machines or humans, WCAG 2 has effectively downgraded those issues that traverse the boundary between usability and accessibility. Sadly this has meant that many of the Success Criteria that are particularly relevant to people with cognitive, learning or reading difficulties are now at triple A, and so largely ignored.

I should make it clear that I am aware that WCAG 2 Success Criteria levels are determined by a variety of factors, and importantly provide an indication of how difficult complying with a criteria is likely to be. In this way, they are very different to the priority levels used in WCAG 1.

However, from a practical perspective, regulatory requirements are based on Success Criteria levels, for example Double A by the end of 2014, and so they have a direct influence on how well people with different disabilities will be able access web content.

Slide 28

So, we have gone from one vague Priority 1 checkpoint requiring the use of simple appropriate language, to three triple A WCAG 2 Success Criteria. Two relate to the use of ‘unusual words’ and ‘abbreviations’, and then we have this dossy:

3.1.5 Reading Level: When text requires reading ability more advanced than the lower secondary education level after removal of proper names and titles, supplemental content, or a version that does not require reading ability more advanced than the lower secondary education level, is available.

While the language used in the Reading Level Success Criteria may be more precise than that used in the WCAG 1 checkpoint, I am not sure it is any more meaningful. But of course, these aren’t the only Success Criteria relevant to people with cognitive, learning or reading impairments.

Slide 29

This is a map of Success Criteria that can have impact on how easy web content will be to read and understand.

By meeting the level A and AA Success Criteria indentified here, content is more likely to be accessible to assistive technology users, as well as people with cognitive and reading difficulties. However, there are also eleven triple A Success Criteria, that are important but often ignored.

For example:

Visual presentation covers many important reading related issues including:

- Line length (ideally not more than 80 characters)

- Don’t justify text causes “rivers of white”

- Text size – not too small. I long for the day when developers stop setting text at 90% or .9ems and leave it at the default or maybe even make it a little larger.

Links: For single A compliance links need to make sense within the context of the surrounding information, however if this surrounding content is hard to read it is of little value. Screen reader users as well as people with reading problems love the text used in links to be clear, concise and meaningful.

When it comes to Headings: The single A Success Criteria 1.3.1 requires headings to be marked up properly and the double A Criteria 2.4.6 says the actual headings need to be descriptive, but Criteria 2.4.10 at triple A is the one that says you should break up long documents into different sections identified with headings.

Readability I have already touched upon

Slide 30

I believe we need to spend a little more time thinking about how different people find information on websites, and how easy it is for people to read and understand that content once they have located it.

I know many of these issues are at triple A, and so not required to get a tick of approval from authorities, but they really are more important than that.

I would now like to return to the issue of older web users that I mentioned a little earlier and give an update on some of the work we have been done in this area recently.

Slide 31

My CSUN 2011 paper reported on the results of an online survey of 124 people over the age of 60, as well as a survey and user-testing with 31 people in Sydney. The oldest person we tested with was a sprightly 93 year old lady.

Nearly all of the participants said finding the information they were after was a major difficulty, with just over 80% saying that when using the web this was a problem sometimes or often. And, perhaps not surprisingly, more than half said moving or flashing content was a problem sometimes or often, with most nominating adverts the main culprit.

50% reported the size or the colour of the text on web pages was a problem.

Slide 32

However, when the people were specifically asked in a later question, if they had difficulties with the colour or the size of text on pages: 48% said that text size was a problem at least some of the time; and, 23% mentioned colour.

These numbers are rather interesting, but much more worrying was the fact that most had no idea how to overcome these difficulties when using a computer.

Many different ways of overcoming the problem of text being too small were offered, the most tragic explanation from a man in his sixties who needed information from a government website. He resorted to printing the pages out at home and then taking them to the local library so that he could make the text bigger by enlarging the page on a photocopier.

Slide 33

Most browsers now have a variety of controls for either increasing the size of text on the page or zooming-up the whole page. However less than 40% of the people we interviewed were aware of these browser tools. And, I suspect that this lack of knowledge is not just confined to people over the age of sixty.

There are website developers who are concerned about accessibility issues, and some sites do provide users with advice on accessibility related matters like how to increase text size. This information is often obtained by clicking a link labeled “accessibility”. During our interviews we asked participants what they thought the accessibility link might mean. And, only 10% appeared to have even a basic idea about what the term might mean in relation to the web.

When also asked about in-page resize tools, which are often icons in the top-right corner of the page. Nearly all the participants maintained they had never ever seen them, this was in spite of the fact that one of the pages used in the testing had the Big-A Lttle-A icons at the top.

Slide 34

I and a number of friends, including Russ Weakley, have been working on this problem on-and-off over the last year. We feel it is likely the solution will have a number of main components:

First, the information need to be easy to understand. And to that end, we prepared a number trial pages with a simple text explanation about what to do and a short video demonstration. These pages are currently in the “Having Trouble Reading This Page” section of my new site

The first page in this section describes the standard and well supported technique for zooming with the keyboard. And contains this short video (shows video).

The second issue was how to get information relating to the myriad of devices and browsers that people use. And for this, we thought it might be possible to turn to the wider accessibility community. The hope is that people who were interested in the general idea and who use different operating systems and browsers, would be willing to prepare simple text instructions and a video describing what is required with the systems they are familiar with. The information from these different sources would need to use the same basic format or template.

Slide 35

Then there is the question of making the information available in a way that will be easy for site owners to implement and users to identify.

This slide outlines the basic concept. At the centre, there is a server where accessibility people can put information about how to change the size of text or the use of colour on a webpage. And on the other side, those site owners and developers who wish to use this information, would be able to pull it down from the server and incorporate it into their sites when requested by site visitors who need assistance.

But this of course, doesn’t address the problem of how do we let site users know a site contains information that might help them, and how to find it.

Slide 36

To answer this question, we came up with the idea of have an icon or widget that site owners or developers could put onto pages. Something like this one shown on a simple mock-up showing the front page of my site. At the top of the page there is a button with the label “Customise this page”.

The words used here are just a suggestion and maybe someone could come up with something better.

Behind this is a tool, there is some scripting that sniffs out the operating system and browser that are being used. And, when the site visitor clicks the button or icon, a dialog appears with information relating to their specific operating environment.

Slide 37

The dialog would provide provides basic options for changing text size and colour using the browser . There would also be a link to making the changes at an operating system level, and probably a link to a page with basic information in case a particular operating system/browser combination can’t be identified.

But, in our example here, the tool has identified the person is using Windows 7 with Internet Explorer 9. And, if the site visitor just wanted to make the text a bit bigger, they would then click the first button, “See how to change your browser’s font size”.

Slide 38

And get a new dialog with a video on how to increase text size and a short explanation of what is required in text.

I imagine this dialog would also contain a link to information about how to make the changes at a system level.

So that is the general idea, and our hope is to have a simple functional example using one or two sites prepared in the next few months.

I have no desire to develop this as a service, but I do believe that it could work and be really beneficial, so my hope is that someone is willing to take it on – maybe one of the vendors, or the W3C, or anyone. So if you are interested or have any suggestions about who might be, please get in touch.

Slide 39

Thank you.

Here is my contact details, you can email me at rhudson@usability.com.au or get in touch via twitter.

Any questions or comments.